This is where the UN Financing for Development (FfD) process comes in – as a space to advance on the systemic changes we urgently need to see.

The FfD process is unique, as it is the only truly democratic space where global economic governance is addressed, while having the issues of climate change, inequalities and human rights at its core.

FfD is neither a pledging nor fundraising process to finance SDG implementation. It is meant to create the policy and fiscal space for developing countries to finance their development in a sustainable way.

FfD has a historical root of arising out of the active discontent of developing countries about the systemic shortcomings of the international financial architecture. Though international economic cooperation is part of the responsibilities of the United Nations, it has been systematically marginalized by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB). Not surprisingly, with developing countries having greater influence in the UN’s ‘one country one vote’ system, the issue of democratizing global economic governance remains at the heart of the FfD process. On the other hand, rich countries prefer to control international economic policy decisionmaking through institutions like the IMF and WB, where they have a larger vote share, or the OECD where they have exclusive membership.

Though the FfD process is a UN activity, the review process includes International Financial Institutions (IFIs) such as WB and IMF, which despite being formally part of the UN system have traditionally escaped adequate responsiveness and accountability to the normative guidance of the UN General Assembly by establishing governance system centered on their shareholders. It also includes the World Trade Organization (WTO), which maintains cooperative arrangements with the UN but is not part of the UN system. This is the reason why the FfD conferences are ‘international’ and not ‘UN’ conferences on Financing for Development. In addition, civil society and the private sector are also recognized as stakeholders in the process, making the FfD process a uniquely inclusive space for discussing the global economic system in all its systemic dimensions.

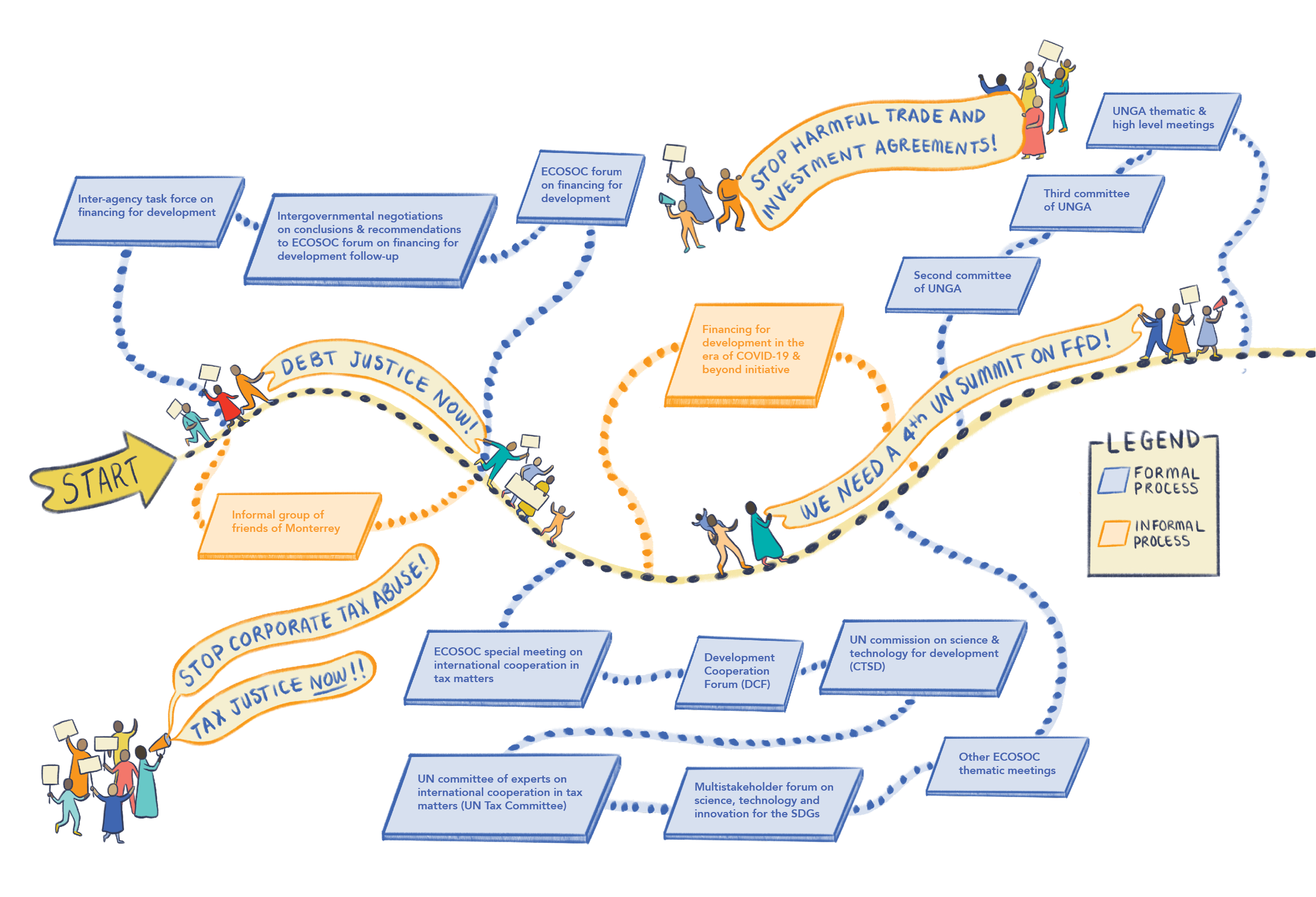

The FfD process is meant to work toward coherent, rights-based, interconnected thematic content, norms and recommendations on global economic governance and the systemic and historical inequalities that define it. It is therefore organized into topic areas to address a range of development finance sources in a holistic manner: domestic resource mobilization; domestic and international business and finance; international trade; international development cooperation and official development assistance; debt; technology; and systemic issues.

Visit here the UN FfD official website: https://financing.desa.un.org/

2002 Monterrey Consensus

The first International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD) happened in Monterrey, Mexico, in 2002 i.e the “Monterrey Consensus”, in the aftermath of the Asian financial crises. The conference was an attempt to recover the UN’s voice on the global economic and financial system.

2008 Follow-up International Conference on Financing for Development to Review the Implementation of the Monterrey Consensus, Doha, Qatar

At the Financing for Development Conference held in Doha in December 2008, member states reaffirmed their commitment to the Monterrey Consensus and unanimously adopted the Doha Declaration on Financing for Development. The second FfD conference was against the backdrop of the 2007-2008 economic crisis that originated in the Global North. For two decades, the net flow of investments had been moving from developing countries into developed countries. In other words, the international financial system was not actually enabling the mobilization of resources for development in the Global South.

2015 Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) Third FfD Conference

The third FfD conference overemphasized the need for bridging financing gaps for the SDGs. The negotiations were fraught with developed countries arguing that the Addis Ababa Action Agenda be reduced to Means of Implementation of the SDGs, while developing countries argued to preserve the FfD process as distinct and complementary, but separate from the SDGs. The final compromise was that one of the goals of the AAAA specifically (not the FfD process) was to support, complement and help contextualize the means of implementation for the 2030 Agenda. But the broader goal of the FfD goes beyond SDG implementation.